What is Harmony in Music? How Notes and Chords Work Together

Harmony is one of the most important subjects in music.

It’s the set of principles that govern how musical notes work together in chords. And how those chords function next to one another in a progression.

With such an important subject, it’s easy to see how new and emerging producers can feel overwhelmed.

But even if you’re just getting started with music theory, there’s nothing to be afraid of once you understand the fundamentals of harmony.

In fact, learning basic harmony can help you develop ideas faster and unlock new creative directions to move forward with your music.

In this article I’ll give an introduction to the concept of harmony and unpack the key ideas to improve your skills.

What is harmony in music?

Harmony is the interaction of two or more musical notes that sound at the same time.

It’s sometimes called the vertical aspect of music for the way notes appear together in visual representations like musical notation or the MIDI piano roll.

In addition to the combination of notes at a given moment in musical texture, harmony refers to the action of chords in a progression as they change.

In this respect, harmony is often used as a shorthand for the overall characteristics of the chords and progressions in a composition.

Relatedly, instruments that are capable of producing multiple notes at the same time are sometimes called harmonic instruments.

In a traditional ensemble, instruments like the guitar or piano provided the harmonic elements of the music from within the rhythm section.

Finally, harmony is used as a casual term to refer to the musical texture created by vocalists singing together.

New music theory?

Brush up on the basics with these guides.

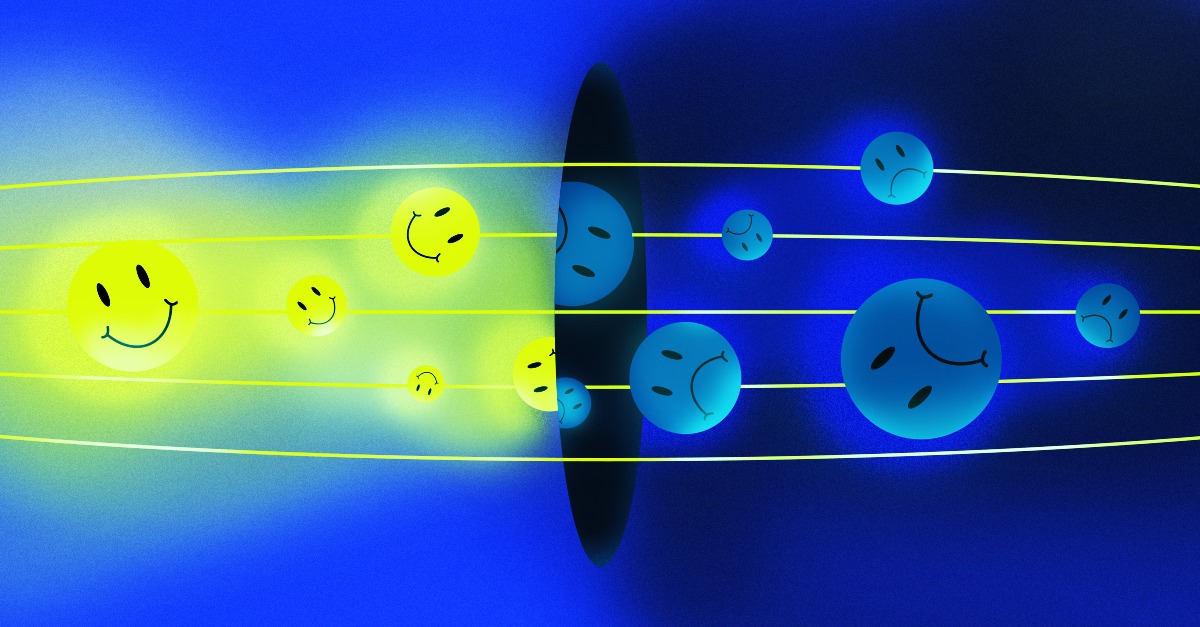

Consonance and dissonance

Musical harmony is grounded in the idea that some notes create a pleasing effect when combined together while others sound harsh and discordant.

Sounds that have a natural sense of musicality with one another are called consonant.

On the other hand, grating, uncomfortable combinations are considered dissonant.

While these qualities may seem universal, there are many factors that influence whether or not we find musical textures pleasing.

But it’s easy enough to classify the basic mechanics behind consonant and dissonant tones in the Western musical scale by evaluating their intervals.

Musical intervals

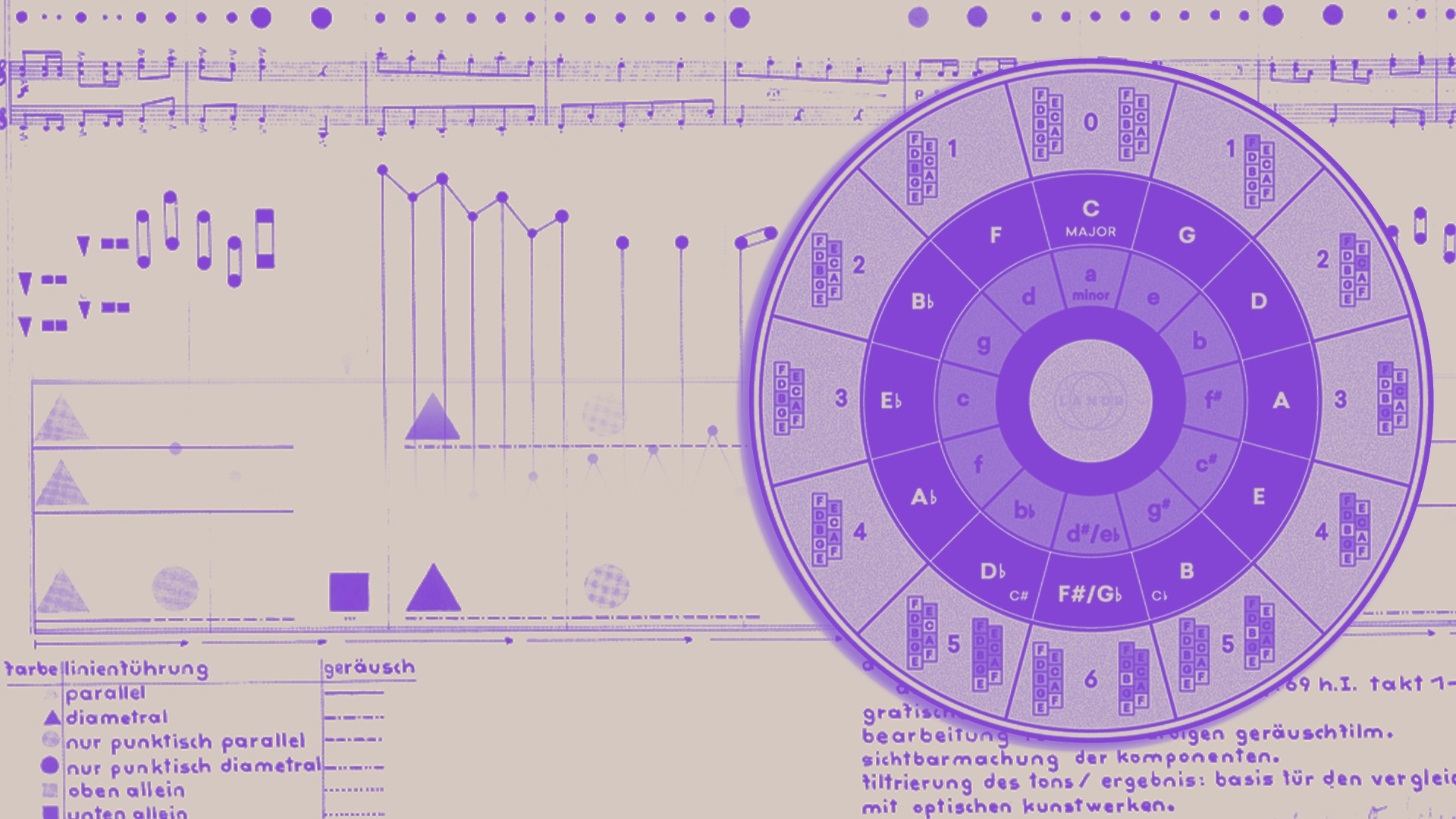

Musical intervals are the foundation of harmony.

They define the relationship between two notes by measuring their distance apart in terms of the musical scale.

By evaluating the number of semitones that separate each note you can assign each interval a number and quality.

For example, the tone located 4 semitones above an initial note is called a major third.

In addition to the number of semitones and their relation to the major scale, the five possible interval qualities are major, minor, diminished, augmented and perfect.

Evaluating interval relationships is central to building and analyzing harmony. On top of that, it’s an essential skill when it comes to ear training and musicianship.

If you need an intro to musical intervals, head over to our in-depth guide to get started.

Chords

Combining notes with different interval relationships is how you build chords.

The simplest chord formula is the triad. It consists of three notes stacked up in thirds.

The qualities of each note in relation to the root determine the overall quality of the triad.

For example, a major third and a perfect fifth away from the root make up a major triad.

If you need to take it step-by-step with building basic chords, head over to our beginner’s guide.

If you’re ready to move on, triads are just the beginning!

Add another third to the stack and you have a seventh chord. The additional tone adds a new sonic attribute that changes how the chord interacts with others in a progression.

You can even keep going by thirds, adding chord extensions and color tones until you have the kind of rich, sonorous harmonic textures found in jazz chord progressions.

On top of all that, stacked triads aren’t the only way to arrange chords.

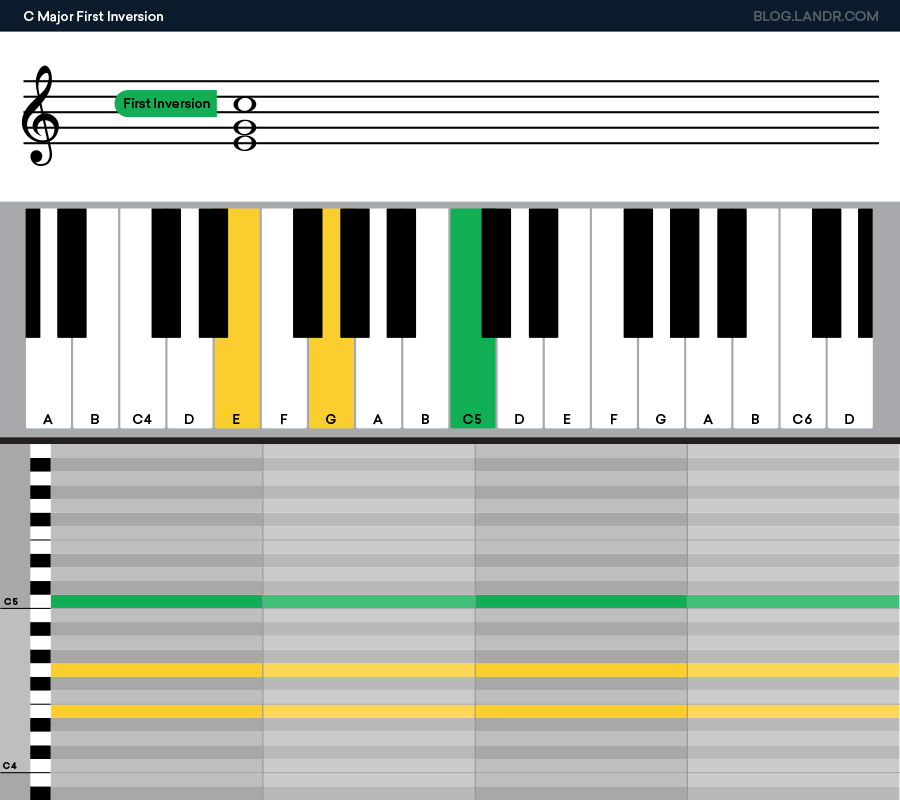

By mixing up the order of the notes without changing the relationship of intervals, a chord can maintain its identity, but be expressed in a different way.

For example, swapping the lowest voice of the chord for a note other than the root is known as a chord inversion.

A triad has two inversions in addition to root position. A seventh chord has three.

If you want to dive deeper on chord inversions, head over to our guide for the full tutorial.

Roman numerals in music

If you’re just seeing music theory concepts for the first time, you may be confused by Roman numerals.

Theorists use them to analyze chords by their scale degree and function.

For example, the chord beginning on the tonic, or first note of the musical scale is written as the Roman numeral I.

I also represents the chord built on the tonic when shown in a progression.

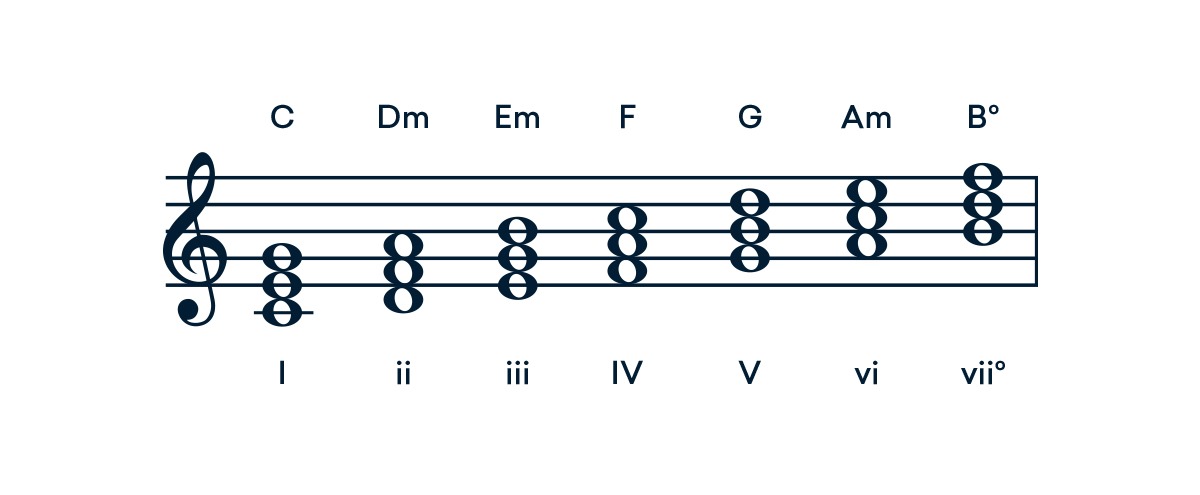

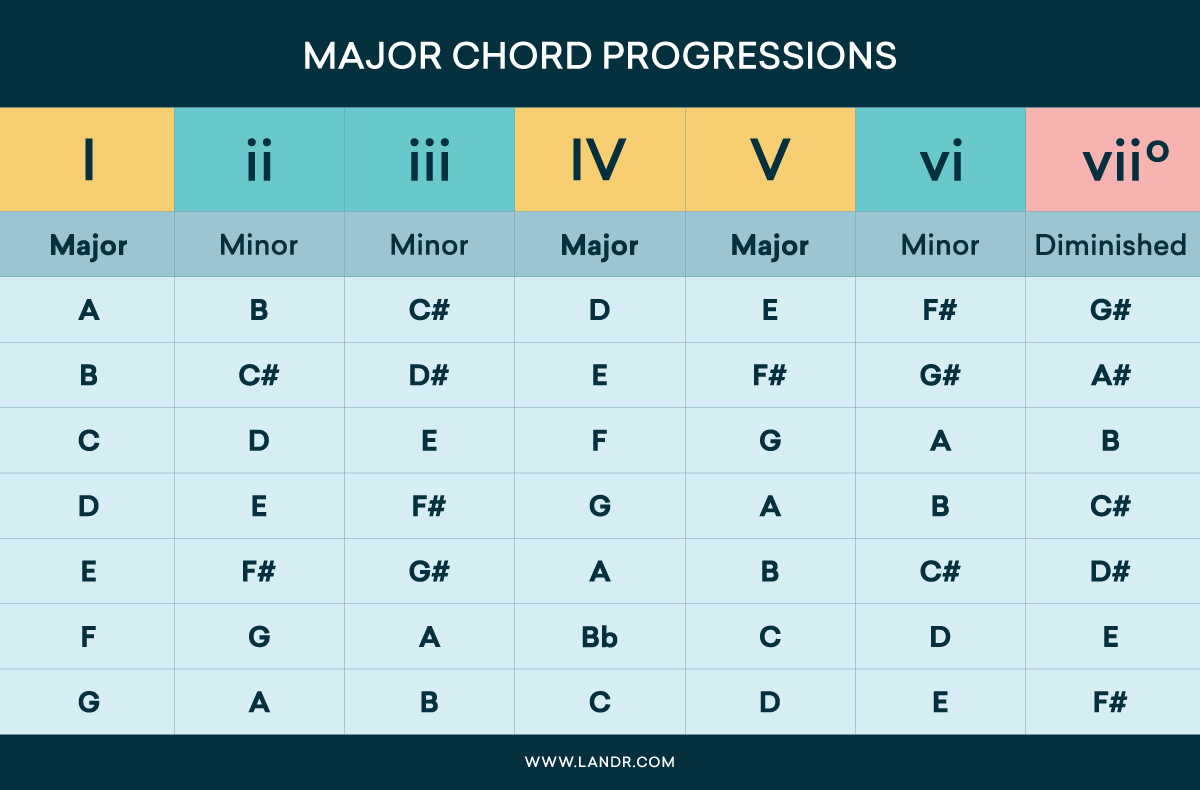

Here are the scale degrees of the major scale, the corresponding Roman numerals and their diatonic chord quality as I explained above.

Functional harmony

Functional harmony refers to the harmonic roles that create the sensation of tension and release in Western music.

With the basics of chords and intervals covered, the next step is to sort the chords of the scale by function.

To understand where functions come from, consider the makeup of the major scale.

It contains two semitone intervals—one between the 4th and 3rd scale degree and the other between the 7th and tonic.

These tones have a natural direction in which they gravitate toward a feeling of stability.

The 4th scale degree wants to resolve down to the third, while the 7th (or leading tone) wants to resolve up to the tonic.

Now consider the dominant seventh chord in the same key. Building on scale degree 5, the dominant seventh chord contains both the 4th and and the leading tone.

These tones give the V7 chord the greatest feeling of tension of the diatonic chords in the key.

With the tonic as the most stable sound, these two chords act as harmonic poles with their own gravitational pull.

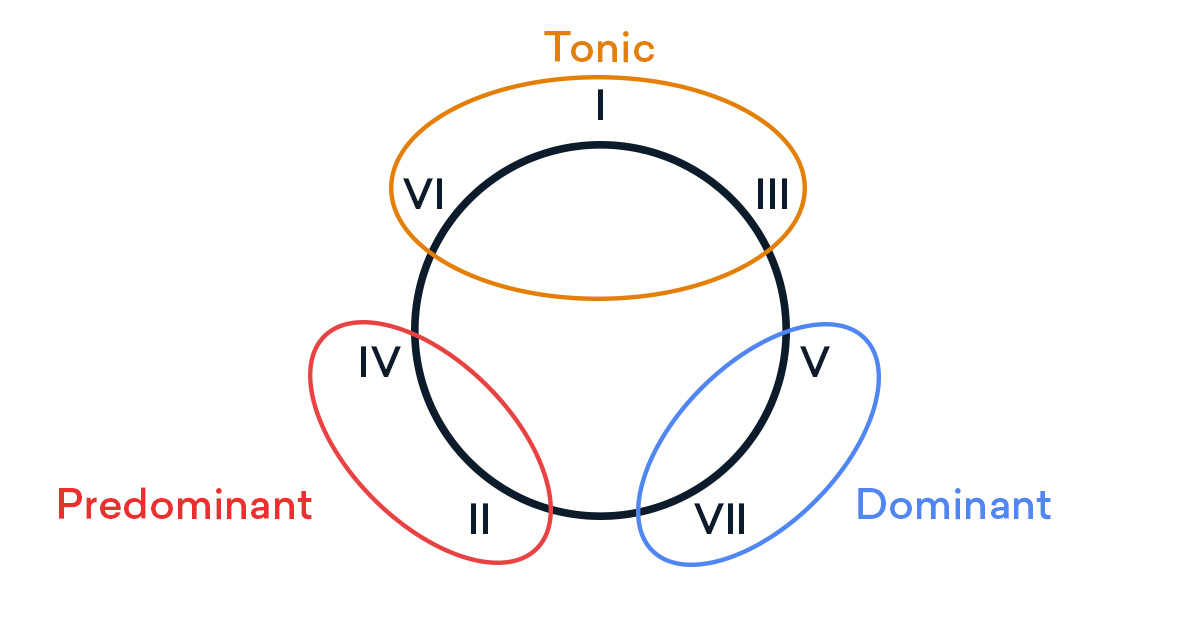

That neatly fits the diatonic chords into three categories—tonic, pre-dominant and dominant.

It also generally describes forward harmonic motion in a chord progression—from tonic to pre-dominant to dominant and then back again!

Here’s each chord in the major scale sorted by functional harmonic role:

When you look at it this way, chord progressions seem much less intimidating!

Harmonic progressions

A harmonic progression is a sequence of chords that progresses with forward motion from stability to tension to release and back again.

They provide the harmonic backdrop for the song’s melody and make up a major aspect of its identity.

If you’re just getting started with music you might find chord progressions hard to learn.

It’s true that they require some background info, but the basics are easy enough.

The first step is the diatonic triads. These are the three-note chords built on each scale degree of the major scale.

Here are the diatonic chords and their qualities in C major.

Next is to sort the triads into functions as we did above.

Now we’re ready to look at some chord common progressions. By marking the chords and their qualities with Roman numerals we can start to analyze the chords and see what make them tick!

Harmonic analysis

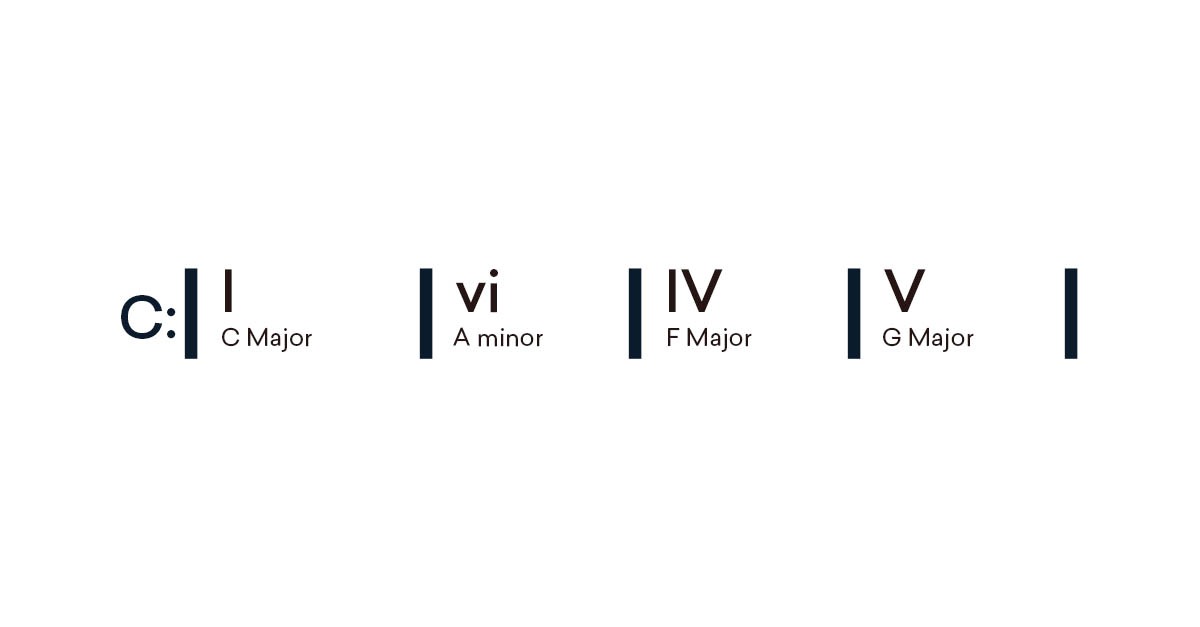

Here’s a well-known and emotional chord progression that’s instantly recognizable.

Sometimes called the 50’s progression, it has a long history of use in vintage ballads like the Righteous Brother’s timeless classic Unchained Melody.

Here are the chords as written in C Major:

Replacing the chord names with their Roman numeral notation, we can easily see what makes this progression so effective.

Beginning on the tonic, the progression moves smoothly to the chord built on scale degree vi.

It’s a minor chord that shares two notes with the tonic triad. In the world of functional analysis, this type of motion prolongs tonic harmony, while developing it with additional richness.

The next move is to IV, which is the strongest pre-dominant sound of the diatonic triads.

Along with the shift from minor to major, this choice makes it clear that the progression is visiting a new harmonic area.

Finally the progression reaches V, concluding its journey towards the opposing harmonic pole.

The tension of V resolves back to I and the progression loops neatly back to stability before embarking again towards tension.

It’s no wonder this classic progression works so well!

Modal harmony

As you analyze more material, you’ll find that not all harmonic patterns are strictly functional.

For example, if you’ve noticed that that dominant 7th chord doesn’t always appear in pop music the way I’ve described above—you’re correct!

One of the key features of pop music as it has evolved to the modern day is a decrease in reliance on functional harmony.

So what else describes the harmonic patterns we see in today’s music? Often, the answer comes from musical modes.

The modes are a unique set of scales derived from the pattern of tones in the major scale. They actually predate the common transposable major scale by centuries.

Modal harmony refers to chord structures that come from the collections of notes in the musical modes.

If you’re new to modes, consider heading over to our in-depth guide for the full story.

Read - Music Modes: How to Enrich Your Songs with Modal Color

Non-harmony?

Another factor to consider when it comes to modern music is an increasing divorce from any kind of harmonic structure.

20th century classical music is notorious for this concept, but it appears often in different ways in contemporary popular music.

Ever heard a song that feels like it stays in the same harmonic area throughout? It’s especially common in electronic music and other genres that rely more on sound texture than harmonic action to communicate.

Many consider the absence of harmonic development to be a form of non-harmony. It can occur when a piece of music rests on a sustained, droning tonal center throughout its duration.

What about a song so far removed from functional tension and release that it has no harmonic clues to point you toward a stable sense of “home”?

It may be that there’s no way for functional analysis to work with this type of material. For situations where none of the approaches seem to fit, you might consider them atonal!

Plenty of modern songs contain elements that blur this line between consonance and dissonance, harmony and atonality.

Perfect harmony

Harmony is one of the deepest structures to study in music.

It’s impossible to even scratch the surface when it comes to the different ways musicians have treated the concept over the years.

But even with so much to learn, getting familiar with harmony is important for every musician and can lead to improved results right away.

If you’ve made it through this article you’ll have a great start when it comes to understanding harmony.

Gear guides, tips, tutorials, inspiration and more—delivered weekly.

Keep up with the LANDR Blog.